Ransomware Comes to Higher Education

Good evening, everyone:

National Public Radio recently aired a fascinating conversation with Spike Lee about his new film Highest2Lowest, which casts Denzel Washington in a story about a kidnapping and ransom plot within the dark corners of the New York music industry. Anything with Spike Lee and Denzel Washington in the same sentence is worth paying attention to. But it also got me thinking more about the deeply disturbing notion of ransom: demanding payment in exchange for the release of something/someone of value.

My mind moves to hospitals’ data being held in ransom by hackers. Or to kidnapped corporate executives. Or to the tragic death of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son.

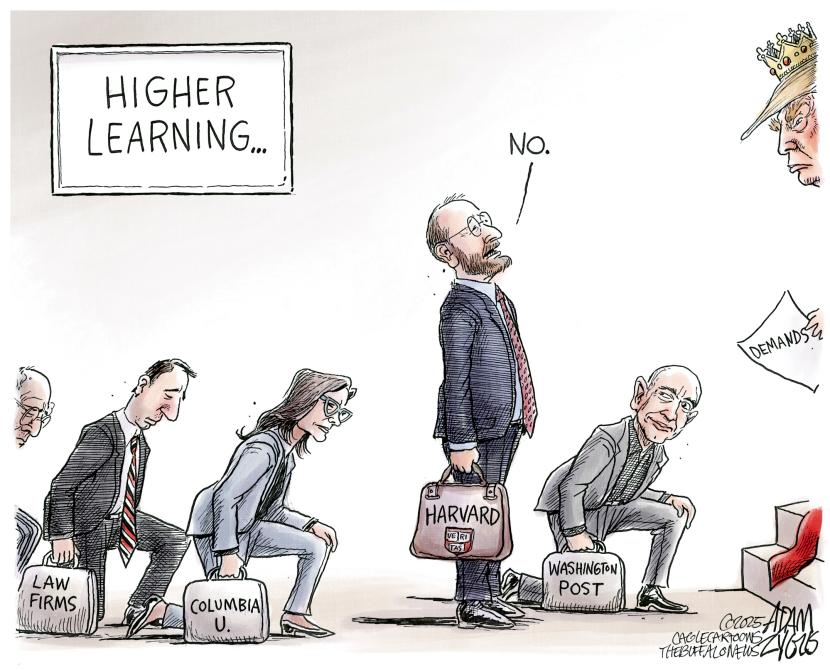

But it then turned to colleges and universities. It is hardly a stretch to see ransomware in the freezing of federal funding to colleges and universities deemed to have engaged in antisemitic activities, pro-DEI curricula, coddling of international students who pose a threat to U.S. security, or other activities inconsistent with “true American values.” The ransom demanded has been both cash payments (collectively well in excess of $1 billion, and counting) and changes in policies and practices on each of the affronting fronts.

There has certainly been intellectual resistance: to the evils of suppressing free speech . . . the undermining of the autonomy of independent pillar of civil society in forming and stewarding their curriculum, hiring, and admissions policies . . . the unraveling and perhaps permanent impairment of research activities that have no relationship to the articulated concerns of the administration . . . . and on and on.

But the cash extraction part – although a transactional setback that can be recouped over time – is no less disturbing. A commentary written by Amanda Carpenter (for a new blog called “The Entrenchment Agenda” within the substack “If you can keep it”) reminds us of what the FBI states in unequivocal terms about paying ransoms:

“The FBI does not support paying a ransom in response to a ransomware attack. Paying a ransom doesn’t guarantee you or your organization will get any data back. It also encourages perpetrators to target more victims and offers an incentive for others to get involved in this type of illegal activity.”

Bingo.

It would certainly seem to me that the reasons that our government shouldn’t – and won’t – pay ransoms would dictate that neither should our institutions of higher education. There is no guarantee that this payment will end the cycle of demands . . . . There is no deal-making involved, only a non-negotiable demand that must be met . . . There is every reason to expect that one institution capitulating to a ransomware demand will lead to other ransomware demands on somebody else, and usually at a higher rate of extraction.

Carpenter argues that there is accordingly only one effective way to resist individualized ransomware demands from a federal government armed with endless sources of leverage, with an apparently insatiable appetite, and with little regard for principled negotiation: collective resistance.

But that is way, way easier said than done. To start with, each institution has its own self-interests to protect. In one, a billion-dollar research project on Alzheimer’s treatments will be destroyed if interrupted. In another, a formal DEI framework can be dismantled with relative ease, but with lasting impairment of equity efforts . And at yet another, board members and alumni with particular ideological predispositions may not give the administration any choice.

And then there’s the extraordinarily difficult challenge of higher education being about as complex and diverse an ecology as it’s possible to image. Organize collectively just among the Ivy’s? How about Stanford? Work together as private, elite colleges? How about UCLA? And on and on.

Carpenter nevertheless argues that higher education should:

Invest in and build a system so resilient that the attacker has no leverage. That requires a mutual understanding that no single institution stands alone and that the attacker must not be allowed to play them off against each other.

It would require a shift from competition to solidarity: abandoning rivalries to form a firewall of mutual support, where institutions present a single, unified front against the aggressor.

Kind of like the NATO Article 5 discussions that took place at the White House yesterday: how to ensure that an attack against one is an attack against all.

Carpenter proposes that in anticipation of additional and continuing attacks on higher education, there might be opportunity to create a pooled legal defense fund . . . or to agree not to settle without some form of cross-institutional consultation . . . or to adhere to a joint communications strategy casting in bright relief the irreparable harms that terminating research funds might have. Still a tall order, however. And with no assurance that it would actually work.

So, this notion of collective resistance may not be practical. But then too, it may not matter whether or not it’s practical. The word “existential threat” is often over-invoked. For our system of higher education, however, it is exactly that.

Rip