Hanging Rhinos and Hairy Truths: Why Science Still Matters

Good evening everyone:

With all the heat and divisive divergence of view about the credibility of science – during COVID, about climate change, and related to issues of authority and expertise generally – I thought I might include a couple of examples of the kind of science that might lead one to skepticism. I wanted to list a handful to provoke your own form of astonishment, and then circle back and explain why deeper analysis of scientific motive is important.

First, why in the world did scientists feel compelled to hang ten tranquilized Namibian rhinoceroses upside-down for ten minutes to see the effects? Where are William Proxmire’s Golden Fleece Awards (given from 1975-1988 to outrageous public expenditures for scientific experimentation) when we need them?

How about measuring an audience’s odor levels in movie theaters during different genres of film.

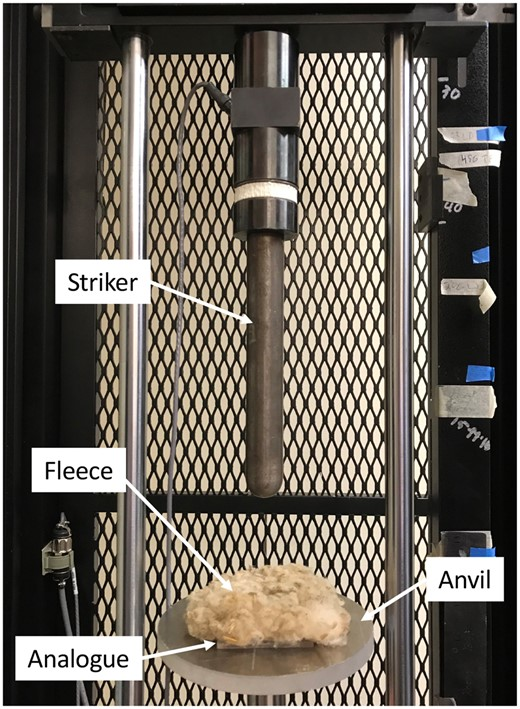

Or, why would we want to know the effects of pummeling sheep fleece glued onto a face-like bone-facsimile?

No wonder people wonder whether the science behind drugs developed with warp-speed is real. Who would trust those guys?

I should admit that my friend Ed Skloot alerted me to these examples, which are actually “Ig Nobel Awards” (readig and noble quickly together for the full effect) issued annually and presented by actual Nobel laureates. The award winners receive a trophy (which they have to assemble themselves from a 3D printout) and a cash prize in the form of a counterfeit 10 trillion Zimbabwean banknote. If you’d like to check their veracity, you’ll have to visit theAnnals of Improbable Research, a science humor magazine.

Here’s the curve-around.

The rhinos first. Turns out that the Namibian Ministry of Environment, Forestry, and Tourism wanted to understand how best to transport black rhinos who are part of conservation effort to promote genetic diversity – they are moved by helicopter out of habitats that have been compromised for one reason or another. The theory was that a rhino’s heart and lung health might be compromised by putting them sideways on a platform:

Sure enough, the scientists found that it was better to transport them back-to-the-ground, legs-up.

When rhinos are transported on their sides, gravity causes the lower parts of their lungs to receive lots of blood, but the upper parts are being deprived – when they’re upside-down, blood flows equally to both parts of the lungs.

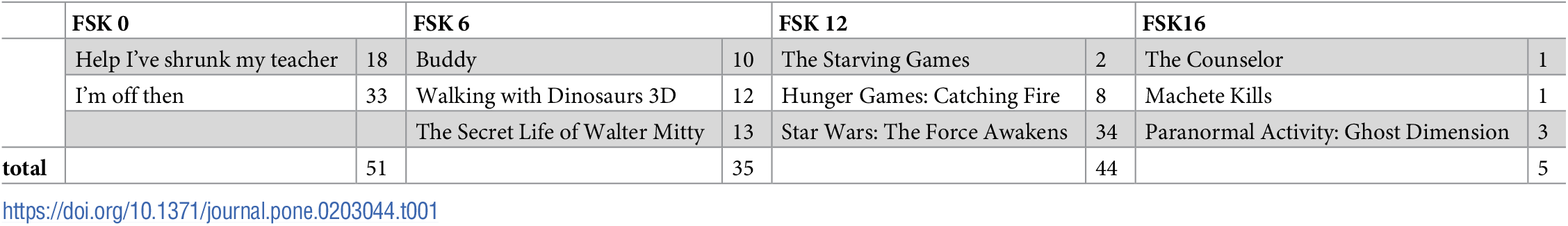

Back to the odors in the movie theater. Evidently, the odors produced by an audience reliably reflect the levels of violence, sex, anti-social behavior, drug use, and cursing of whatever film is playing. The title of the research papers suggests why that might be useful: “Cinema Data Mining: The Smell of Fear.”

Translated, I think: the chemicals given off during movies might be seen as a proxy for the kind of emotional tension that could aid in attaching age classifications to films. Alternatively: breathalyzers as an entirely new way to determine what films your teenager actually did watch with their friends last Saturday when you were at dinner.

And finally, the sheep-fur punching bit. Charles Darwin had proposed that men’s beards were possibly an “ornament” that served to attract females. Not so fast. Three scientists from Oxford begged to differ, suggesting that beards were actually initially grown to protect the face, throat, and jaw from lethal attacks. As the researchers noted, “the mandible, which is superficially covered by the beard, is one of the most commonly fractured facial bones in interpersonal violence.” By measuring the force able to be absorbed by a sheep’s fiber without fracturing the bone substitute, the scientists figured out that the best way to absorb a punch is to look like John Barker.

Or, because they don’t know John, they put it slightly differently: “Tissue samples were prepared in three conditions: furred [i.e., John], plucked[i.e., Aaron], and sheared [i.e., me]. We found that fully furred samples were capable of absorbing more energy that plucked and sheared samples.”

Bottom line: trust the scientists.

Rip